Reflecting on the inclusion of women in Rwanda’s post-conflict peace process, where has the country done well and where is there room for improvement?

In 1994, the world would have never thought that Rwanda—a country that had erupted overnight into genocide—would later be known as a post-conflict exemplar of gender equality. Yet, this reputation is easily justified. After the genocide, women’s groups in Rwanda reached across ethnic divides, engaging women in peacebuilding and reconciliation. A constitutional gender quota of 30% was set for women in the Rwandan parliament. Today, women making up nearly 64% of the seats in the lower house. The country is heralded as the “best place to be a woman in Africa” and was granted the international “Women in Parliament” award in 2013.

Changes such as women’s inclusion, gender quotas, and community-level workshops on harmful gender norms and practices promote a level of equality that greatly surpasses the average on the African continent. However, there continues to be room for improvement. Specifically, greater freedom of speech and inclusion of a wider variety of women would improve the impact of women’s participation in politics. In commemorating the genocide this year, it is critical to recall both Rwanda’s successes and the obstacles it continues to face in striving for gender equality.

Women’s Inclusion in Post-Conflict Dialogue

Women in Rwanda were key players in bringing the country to peace. After 1994, women convinced their husbands and relatives to put down their arms and even negotiated surrenders between rebel militiamen and government troops. As ex-combatants, women reached across former divisions to create peace. Women fighters in the Rwandan Patriotic Army and former female combatants of the rebel Rwandan Armed Forces put down their arms and formed associations for reconciliation. Later, women mobilized to participate in community-level gacaca courts or “justice among the grass,” helping to bring their communities toward restorative justice by facilitating local trials that focused on truth and healing. In some cases, they served as judges.

The Utility of Gender Quotas

Data suggests that gender quotas correlate with improved attitudes about women in leadership. Rwanda is a prime example of this theory. The country’s 30% gender quota was enacted in 2003, and by 2010 women made up 57% of parliament. At the same time, there was a notable improvement in women’s symbolic representation in the country, in the social and cultural impact of women in parliament as well as perceptions of women throughout the country. While Rwanda ranks first for its proportion of women parliamentarians in Africa, it is important to note that the countries following it in the rankings are other post-conflict countries. The five African states with the greatest female parliamentary representation, in order, are Rwanda (currently with 55.7%), Senegal (41.8%), South Africa (41.3%), Mozambique (39.6%), and Namibia (36.3%). Each has implemented gender quotas during or after peace processes. In this way, conflict can be a catalyst for women’s rights and inclusion.

Local-Level Transformation

Notably, the Rwanda National Gender Policy was drafted to incorporate gender mainstreaming into government programming and to ensure that gender inequalities are addressed at the umudugudu (or village) level.

Among these umudugudu-level initiatives is the Rwanda Men’s Resource Center (RWAMEC), which tackles gender inequalities, sexual and gender-based violence, and cultural constructions and practices of gender through workshops and mentorship programs for men and boys. Similar programs, such as the Men Engage workshop, have sought to educate men on gender equality and gender-based violence. Other organizations, such as the Rwanda Women’s Network, focus on women’s economic empowerment as a path to greater equality.

Diminished Importance Given to Other Forms of Diversity

While the Rwandan political leadership is comprised by a majority of women representatives, many of these women have relatively homogeneous backgrounds. Many are wealthy, urban, and Anglophone. While mentioning Rwanda’s former ethnic groups of Hutu and Tutsi is now illegal, these characteristics notably indicate the majority of women in the Rwandan parliament are Tutsi and have close ties with President Kagame. And although President Kagame insists there are no ethnic divisions in Rwanda—declaring instead that the population is all Banyarwanda (or all Rwandan)—some have interpreted this as an erasure of ethnic identity that does little to eliminate very real divisions. Instead, reinforcement of uniformity means that only some women are represented in politics—leaving out rural, poor, and Hutu women.

Restricted Freedom

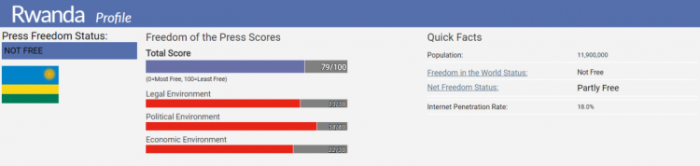

Beyond the blurring of the country’s ethnically charged history, Rwanda faces another challenge in its overarching restriction on journalism and freedom of speech. In 2017, Freedom House declared that the status of the press in Rwanda was “not free.” The country received a total Freedom of the Press score of 79 out of 100, with 100 being the least free possible score. Critics of President Kagame and the Rwandan government have gone missing or been assassinated. Restricted freedoms of speech, the country’s ranking as an authoritarian regime, and President Kagame’s long stay in power do not bode well for the genuine advancement of marginalized voices.

Rwanda’s Freedom of the Press Scores by Freedom House

This is evident in instances such as the 2017 arrest of Diane Shima Rwigara, who was sentenced to 20 years in prison after campaigning against Kagame. Likewise, Victoire Ingabire was imprisoned for running for the presidency in 2010. After being the first woman to run against Kagame, Alvera Mukaramba threw her support behind him the day before the election in 2003.

What Would Better Equity Look Like?

There is clear numeric evidence that at least some women are gaining greater power and equality in Rwandan governance. However, genuine equality would require acknowledging and elevating the voices of all women. For Rwanda to reach a point of true equality, the country will need to consider ways to increase the diversity of women at the table and allow them a platform to speak their truth.

Article Details

Published

Topic

Program

Content Type

Opinion & Insights