With good data comes better policy. It is the hope of Our Secure Future that this new index will allow for more informed decision-making, policies that better empower and include women, and a more peaceful world.

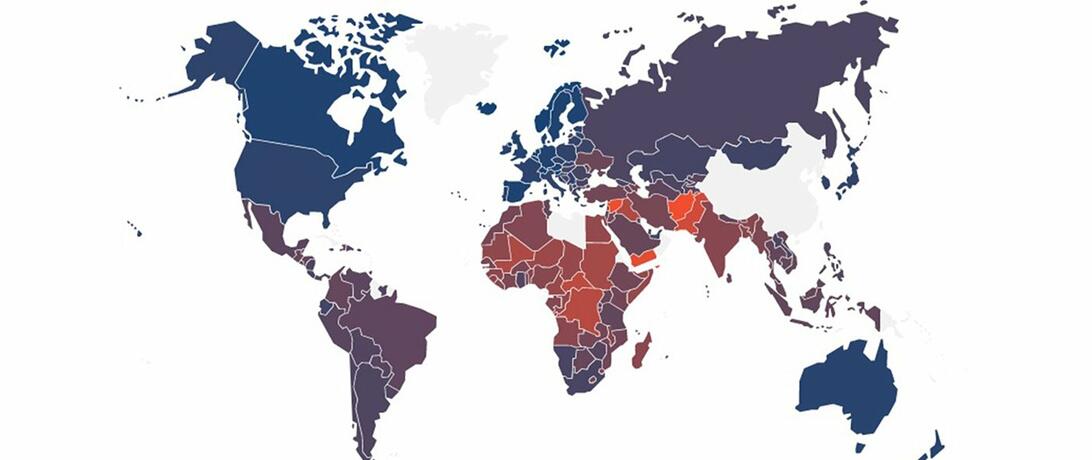

In 2017, the Georgetown Institute for Women, Peace and Security and the Peace Research Institute of Oslo (PRIO) joined forces to publish the first Women, Peace and Security (WPS) Index. Updated biannually, the index will provide unique and vital information to “inspire further thought and analysis, as well as better data, to illuminate the constrainers and enablers of progress for women and girls to meet the international community’s goals and commitments.” The index provides a variable set that measures the rights and security of women and girls in 153 different countries. Each indicator is based on the United Nation’s Sustainable Development Goals and is either a goal or indicator straight from the UN’s sustainable development agenda.

Countries are scored on a scale from zero to one with zero being the lowest possible score and one being the best possible. Then each of the 153 countries are ranked according to their overall score.

What Will This Index Do For Women and Girls?

The theory of change behind the index’s ranking system is called “scorecard diplomacy.” Ranking countries—particularly when also outlining action steps for states to improve their scores—can be a powerful motivator for change. However, there have been sharp critiques of scorecard diplomacy, mainly that scorecards can be ideologically loaded or inconsistent or even encourage countries to “game the rankings,” according to Judith Kelley of the Sanford School of Public Policy at Duke University, instead of making genuinely transformative improvements. While these outcomes are always a possibility, it is the hope of Our Secure Future that reliable data and reporting will help hold states accountable, and push policy decision-makers to incorporate a gender perspective into their daily work. Regardless of the specific impact it will have, we feel confident that the index will be an agent of change in the WPS agenda. We look forward to the real policy improvements that will be made possible through better data on the status of women worldwide.

What Did Our Secure Future Take Away From It?

The vision of Our Secure Future is a more peaceful future transformed by women’s full participation. As such, we focus more on inclusion—and specifically in governance and other decision-making systems—than we do on the index’s other categories. The index is one of many tools that measures parliamentary inclusion, but also provides insight into women’s inclusion at other levels of society. For example, the WPS Index report explained how access to cellphones ensures women’s inclusion in an increasingly digital world. Likewise, other indicators in this category, such as education, employment, and financial inclusion are linked to women’s ability to seek out and win electoral seats.

At the same time it made the case for greater female representation, the index argued that justice and security were at the core of women’s wellbeing—a statement which is supported by the increasing evidence that the treatment of women is directly linked to the behaviors of states. Indicators such as legal and social discrimination against women, and son bias (the extent to which the number of boys born in a given state exceeds the rate of girls), were linked to the risk of violence in more masculinized cultures. The index noted that son bias led to higher levels of military recruitment and mobilization.

Likewise, security variables such as intimate partner violence, perception of community safety, and organized violence seemed to show the same correlation between the treatment of women and overarching political violence and state safety. For example, there appeared to be a distinct relationship between battle-related deaths and the rate of intimate partner violence (IPV) within states.

However, the only two indicators that did not appear to have a positive correlation were IPV and women’s parliamentary representation. In countries—and particularly developed countries—with higher scores across the inclusion dimension, IPV was generally much higher. Iceland, for example, was the top-ranking country and received a perfect score on each indicator with the exception of IPV. Similar outliers in the top ten countries with lower IPV scores include Norway, Finland, Canada, the Netherlands, and Belgium. According to the WPS Index, one potential explanation for this anomaly is that better inclusion and rights for women might be causing backlash in domestic relationships. Alternatively, the authors of the index suggest women might feel a greater sense of comfort coming forward with testimony about sexualized violence in societies that are generally more inclusive and secure.

With good data comes better policy. It is the hope of Our Secure Future that this new index will allow for more informed decision-making, policies that better empower and include women, and a more peaceful world.

What do you think about the new Women, Peace and Security Index? We would love to hear your thoughts on Twitter with @OurSecureFuture #WomenPeaceSecurityIndex.

Article Details

Published

Topic

Program

Content Type

Opinion & Insights