Evidence shows that the presence of women in peacekeeping operations has a positive effect. Yet, the number of female peacekeepers sent to the field remains low.

The evidence shows that the presence of women in peacekeeping operations has a positive effect on its missions. However, despite the United Nations request to its members that it increase contributions from females in every mission, the numbers of those sent to the field remain low. Current operations show little improvement. While the increased presence of women in military units would be a sign of equality that may help to improve the status of women in the host nation, it does not guarantee that local women’s needs will be met. Therefore, it is clear there is a need for gender mainstreaming to be implemented in all aspects of peacekeeping missions.

To understand the need for better mainstreaming, we must understand the history. As stated above, the inclusion of women in peacekeeping forces has grown slowly over the years. Between 1957 and 1989, just 20 women served as UN peacekeepers out of 26,250, or 0.07 percent of all forces. At the end of 2000, women constituted just three percent of military personnel and four percent of civilian police personnel. [1] By 2008, of the 77,117 military personnel in peacekeeping operations, only 1,640 were female, around two percent. [2]

Women are also still lacking in leadership positions in peacekeeping missions. There have only been three women heads: Margaret Anstee in Angola, Angela King in South Africa, and Elisabeth Rehn in Bosnia and Herzegovina.

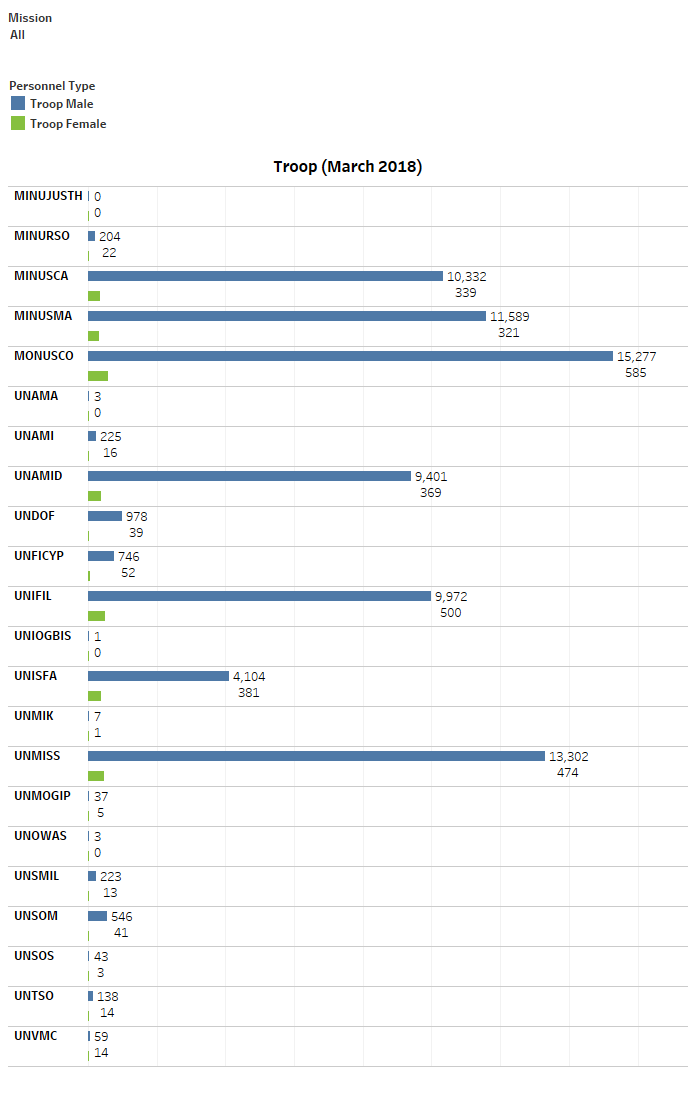

Below are the most recent charts reflecting female military personnel in all active UN peacekeeping missions.

Image courtesy the United Nations Department of Peacekeeping Operations

Despite the low numbers of female participation, some UN peacekeeping missions got it right in terms of having a fully implemented gendered lens. The United Nations Observer Mission in South Africa (UNOMSA) was one of the three missions that has been led by females. This mission was one of the few countries where, through the local structures, women played a significant role in the peace process. The mission was able to achieve a greater gender balance (50 percent of staff were women) and it helped local women feel as if their concerns were being heard and met. Another operation that had a significant gender focus was the United Nations Transition Assistance Group, stationed in Namibia from 1989 to 1990. The personnel consisted of 40 percent women.[1]

A study done by Gender Links found that if at least 30 percent of mission personnel are female, local women are more comfortable joining peace committees, which make them more responsive to female concerns.[2]

The small increase of women peacekeepers over the past few decades shows that we still have a long way to go. It has also been shown that the inclusion of women within peacekeeping does not appear to change those institutions’ fundamental male structures or cultures.[3] There needs to be renewed efforts and funding to implement gender mainstreaming in peacekeeping.

Gender mainstreaming is essential for the success of peacekeeping because it helps operations respond to different security needs within the society, improve operational effectiveness, create a representative mission, strengthen civil components of the mission, and strengthen democratic oversight.

Much discussion remains about how to implement mainstreaming in different peacekeeping contexts. However, there are important areas in which specific gender considerations need to be built in:

- Make it clear that the UN cannot be neutral on gender matters and that it should encourage participation by local women.

- Create clear gender targets for selection and recruitment across all positions and departments.

- Planning and operations need to always include women during missions. [4]

Training also needs to have a clear gendered lens. While the UN Department of Peacekeeping Operations did standardize a generic gender training module within its human rights training module, its resources vary depending on the mission.[5]

To realize its full potential, gender mainstreaming should address the roots of the organizational structures and make changes based on feedback from the local level. This includes training that is implemented fully with gender mainstreaming as well as behavior monitoring. There should also be an active working relationship between civil society groups, who are often on the front lines working to ensure basic human rights, and the local population.

[1] Ibid

[2] Bertolazzi, Francesco. 2010. Women with a Blue Helmet: The Integration of Women and Gender Issues in UN Peacekeeping Missions. Santo Domingo: United Nations International Research and Training Institute for the Advancement of Women.

[1] Links, Gender. 2002. Mainstreaming a Gender Perspective in Multidimensional Peacekeeping Operations: South Africa Case Study. Case Study, Johannesburg: Gender Links.

[2] Ibid

[3] Mazurana, Dyan. 2003. "Do Women Matter in Peacekeeping? Women in Police, Military and Civilian Peacekeeping." Canadian Woman Studies 64-71.

[4] Bertolazzi, Francesco. 2010. Women with a Blue Helmet: The Integration of Women and Gender Issues in UN Peacekeeping Missions. Santo Domingo: United Nations International Research and Training Institute for the Advancement of Women.

[5] Bertolazzi, Francesco. 2010. Women with a Blue Helmet: The Integration of Women and Gender Issues in UN Peacekeeping Missions. Santo Domingo: United Nations International Research and Training Institute for the Advancement of Women.

Article Details

Published

Written by

Topic

Program

Content Type

Opinion & Insights